Three-Stop City Loops

Three stops are enough to shape a day in a heritage city. More than that, and attention scatters; fewer, and you risk missing the thread that ties a place together. This article sets out a plain method for choosing three strong stops, linking them with short, readable paths, and building alternates for weather, energy and crowds.

Choosing the three

Start with a type, not a list of must-sees. Pick one high point (a tower, a hill, a gallery with a view), one room of depth (a museum room or chapel where you can stand still and learn), and one square for breath (a courtyard or close where the city’s rhythm becomes clear). The combination should tell a small story about the place without forcing you to run. If a city is famous for a single monument, do not let it consume the whole day; place it as either the high point or the room of depth, then balance it with the other two.

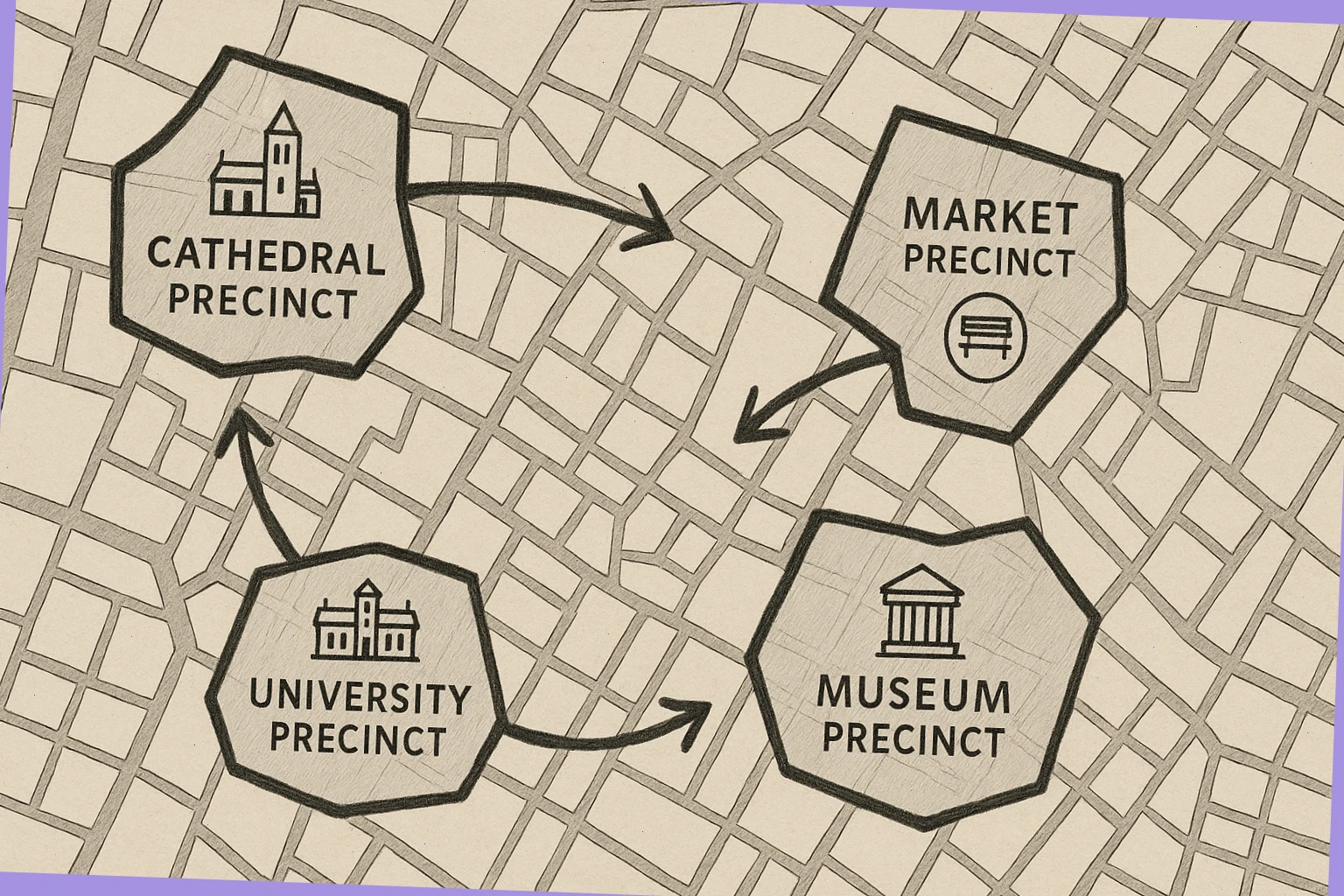

Tracing the links

Draw lines between the three stops on a pocket map. Look for covered links that help on wet days, for gentle gradients if steps are hard, and for streets where noise falls away for a minute. The path between stops is not filler; it is where the city explains itself: shopfronts that follow older plots, arches that hint at lost walls, windows that change height as a hill rises. Keep links short enough that conversation survives the walk.

Timing

Give each stop a clear window. Forty minutes is a workable default for the room of depth; twenty to thirty for the high point; ten to fifteen for the square. The gaps between are your margins for crowds and rain. If a queue grows, invert the order. If a talk overruns, take the square first and return later. A loop succeeds when it remains adjustable without breaking the day.

Families and access

If you travel with a buggy or prefer fewer steps, draw your links along wider gates and smoother surfaces, and mark benches or cafés that allow a short pause under cover. Ask stewards about lift locations and step-free entries; many have printed sheets with diagrams. If a stop presents tricky access, swap it for an equivalent nearby: a chapter house instead of a tower, a low gallery instead of a crypt, a museum room reached by lift instead of one reached by a stair.

Weather alternates

Every loop should have a wet-day version. Covered ways, colonnades and arcades become your friends. Museums that sit between the other stops help you absorb a shower without collapsing the plan. On bright days, seek shaded edges and time the high point either early or late when heat and glare soften.

Reading the city while you move

Carry three cues in your head: alignment, light and order. Alignment finds Roman or early plans that still control streets; light explains Gothic choices that lift eyes and pull weight outward; order helps you see Georgian rhythm and how façades tame space for daily use. With these cues, the walk itself becomes a lesson without requiring heavy vocabulary.

Group dynamics

Small groups benefit from rendezvous points at each stop. If one person wants to visit a side chapel while the rest prefer coffee, set a time on the square and keep the next link short. Agree on a simple signal (a message or a pin). The loop is robust if it allows small separations without losing pace.

Examples

A cathedral city might give you: high point—tower view; room of depth—choir stalls and east window; square—close with quiet lawns. A castle city might give you: high point—motte or keep; room of depth—museum armoury; square—quay with a long edge where people drift. The labels change with place, but the structure holds.

Ending well

Finish near a bus link or station so leaving is easy. If energy remains, add a fourth short stop as a bonus rather than stretching the core loop. Ending with breath—on a square or by water—often makes the memory sharper than ending with a queue.

Contact: [email protected] • 441 524 739 864 • 9 Castle Hill, Lancaster LA1 1YN, England.